9/11, Remembered, Explained

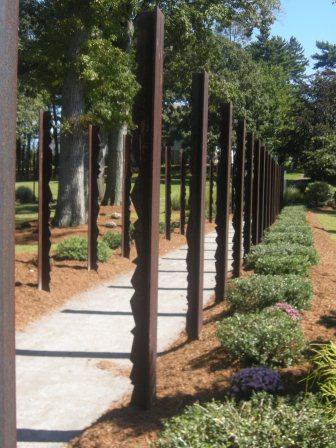

A couple of weeks ago, I took my boys to a local park in our town — it’s a big park, with a handsome art museum on the grounds, a couple of nice playgrounds, tennis courts, duck ponds (populated by geese mostly — which means much of our time spent there is punctuated by me shouting: “Watch out for the goose poop!”) and so on. They’d taken their scooters and I was ambling along while they scooted on the paths, until we reached the museum, in front of which is a memorial to those from our town who died on 9/11. It’s a pretty fair number — we’re only a hour from New York City, so the list is populated with firefighters and police, as well as folks who had worked in the World Trade Center. The memorial consists of a series of metal sculptures — rusty-looking geometric forms, about as tall as a grown man — set in two lines that create a path. At the end of the path is a small rock garden, with two narrow Lucite towers meant to represent the actual towers, and between them a waterfall. It’s pretty, peaceful and not at all morbid:

The boys scooted over and while James was more interested in finding out if he could walk on the rocks (no), Daniel got stuck at the sign explaining the memorial and listing the names (he likes lists, of pretty much anything). He asked me who the people were, so I told him. I said that on September 11, nearly 10 years ago, before he was born, some bad people flew planes and crashed them into these two very tall office towers in New York City.

In an almost-nine-year-old’s ears, a few details resonated, and prompted a few further questions:

How tall were those buildings? Had you ever been there?

Did the guys on the planes die, too?

How many people died? Did you know any of them?

All, it struck me, relatively easy to answer. He didn’t ask — at least not until about a week later — the hard question: why? On that score, I relied on the advice usually given when young kids ask about procreation: Only answer, as simply and clearly and honestly as you can, exactly what you perceive they’re asking, and no more. So I said that there are some people in the world whose ideas about how the world should work and look make them hate our country, and want to hurt us and others like us. I mentioned that these people are rare in the world, and that Americans are not their only targets (I mentioned bombings in places like London, and Madrid, and the embassies in Africa).

And of course I told him that he had nothing to worry about. Which is, of course, a lie.

My eldest is not a 9/11 baby, as children born right before and after the attacks are called. He was in the planning stages, actually, when the planes hit. I am not 100 percent sure of this, but I think the oddest, most random details of that day that live in my memory do so because I was, at the same I was mourning it all, trying to make him. That very day, in fact, was the first one I’d said, out loud to anyone other than my husband, that I was going to try to have a baby.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I got up as usual in my (well, our — I’d been married just shy of one year) apartment, and got ready for my day. It was to be a slightly unusual day, as I wasn’t heading directly to my office, where I was executive editor of Bridal Guide magazine, but was instead going to Bryant Park, to a runway fashion show in the tents there. It was Fashion Week in Manhattan, a yearly Very Big Deal if you’re in the fashion industry, or tangentially attached to the fashion industry, as many magazines are. Even though the show I’d be going to wasn’t in any way related to bridal fashion, our fashion editor had gotten tickets, and because she couldn’t attend herself, she offered them to me, to our art director, and to her assistant. I was going to meet my two other colleagues inside the tents for a 9:00 a.m. show. It was Liz Lange, the maternity fashionista, and it was her first-ever Fashion Week show.

Funnily enough, she was debuting a new line, in partnership with Nike, of maternity exercise wear. I say funnily enough, because it was exactly one week before this show that I’d taken my last birth control pill. It was also going to be the day I shared this otherwise private information with my friend Robin, who was our magazine’s art directior, the mother of one, and the one person I knew who was most interested in when I’d join her ranks and just get pregnant already. I told her while we sat in our seats waiting for the show to start.

Other odd details that run as clear as a DVD in my head:

Earlier, on the train into the city, I saw the smoke downtown. I traveled in from Queens, just across the East River from Manhattan, and I took the Flushing #7, not my usual line, to get to Bryant Park. The 7, before it ducks under the river, curves around and gives riders lucky enough to be looking a gorgeous midtown-to-downtown skyline view. And I saw the smoke and wondered, but only briefly, what that was about. Then we rumbled underground.

On line at the Bryant Park tents, a woman standing behind me took a cellphone call (imagine; cells were not ubiquitous yet, and there were no Smartphones. People actually walked around with their heads up, not down!). She hung up and said to her companion, “My friend said there was some kind of explosion at the World Trade Center.” I wondered, but again, only briefly. Then the doors opened and we filed in.

After the show — already nearly 10 a.m.! — my colleagues and I went down into the subway station to catch an E train up, two stops, to our office. A bike messenger approached me: “Have you been waiting long for a train? I heard there were some problems because of the explosion downtown.” Hmmm. “No,” I told him, “we just got down here so I don’t know if it’s been a while.” I wondered briefly. Then the train, miraculously, arrived –and took us up to 53rd St. without incident.

Then you know how the whole world shifts and you can feel it before you know it? We emerged from the station, where there was often a guy selling knockoff handbags on a folding table. He had a radio, and a bunch of people were gathered around it. I didn’t hear anything, but I knew, and suddenly, that the world I stepped into at the tents at Bryant Park had changed into something else entirely. Then a bystander gave my stunned colleagues and me the shorthand: a plane hit one tower. A second plane hit the other one. One fell down. The other fell down. I looked south down Madison Avenue and I saw it: the smoke. I ran to my office, not even thinking yet, “where is my husband? How will we get home?”, and when I saw him, my husband, in my office, looking for me, it all hit.

Much later that night, after we’d walked back home over the 59th St bridge and through Long Island City to our apartment in Astoria, after we turned on the TV and sat like zombies watching over and over and over the improbable images that still don’t feel real, after I’d finally managed to talk to my parents and find out that my brother, who lived in Washington, D.C., was safe, my cousin called me. She had just given birth, exactly a month earlier, to her second daughter, Ava. Her voice was cracked and hoarse, as she’d been on the phone for hours after we got phone service back, trying to reassure herself that everyone was accounted for.

“It’s the baby’s one-month birthday,” I said.

“Why am I bringing life into a world like this?” she said, hoarsely and dramatically.

And here I was, trying to do the same thing.

But it still felt like the right thing to do.

And now I realize, 10 years on, that I’ve been waiting all this time to explain to the child I eventually conceived that the world before is different than the world after, but that he’s no less precious, and may in fact be moreso. I’m glad I explained the memorial to him in the park that day earlier this summer. I want him to ask more questions, to read and re-read the names and look at the waterfall, and think.

People are starting to talk, now, about media overload in this tenth-anniversary year. Can’t we move on? I’d argue that my sons are, just by their very nature as children born after 9/11, two living, breathing symbols of my having moved on (and that cousin with the one month old second child? She went on to have two more in the years since). But I don’t want to move on, not just because I don’t want to forget (which I can’t) or that I believe none of us should forget, ever (which we will and we won’t), but because we have to keep talking about it, because there will always be new kids to show the memorials to, and because there will always be stories we’ve not yet heard, or considered.

What’s your story?

September 9, 2011 @ 4:01 pm

My story echoes yours, in the procreation way. I was woken up by my husband across the country in Kansas — an hour behind the east coast — to hear the news. We, too, had been married just less than a year. We knew we’d have kids someday, but hadn’t decided on a plan of action. That day, after everything else, the thought that crystallized was that our purpose on this Earth was to leave better people behind us to take care of it. And so we stopped BC, and a little less than a year later, my 9/11 baby — I do call her that — was born.

Not sure when I’ll tell her.

September 9, 2011 @ 9:27 pm

I lived in Astoria, too, then–we might’ve been neighbors. Usually I took the R train, but I stopped to vote on the way to work & took the N instead. When the train went around that curve, where the skyline suddenly becomes visible, people started to murmur & point–the first tower was already hit, and smoke was streaming out of it. It looked like a giant lit cigarette. By the time I came above ground in midtown the second tower was hit, too. People were just standing around on Park Avenue, not doing the NYC Walk of Purpose. That was utterly disorienting to me: New Yorkers were not acting like New Yorkers. We watched the towers fall on the tv in my boss’s office, and my assistant, a sweet, recent grad who’d moved to NY from southern California just a month or two before, became absolutely hysterical. I don’t think it had ever occurred to her that something bad could happen, period, and this wave of fear swept through the room, “Oh my god, we’re in a skyscraper of sorts–are we a target, too?” I could go on and on, as can everyone else, so I’ll just stop by saying that by January 2002 I was out of corporate life, presumably forever.

September 12, 2011 @ 12:21 pm

September 11th was a beautiful day. I was wearing a rust colored skirt, a brown top, and brown enzo angiolini shoes (i.e. not so good for walking long distances). I got to work around 8:45 and as I was booting up my computer, a friend from Boston called me. A plane had hit the World Trade Center. Was it an accident? No one seemed to know. I hung up and walked into my colleague’s office – she always had one of those battery-operated radios. She turned it on and we started to listen. More and more people gathered in and outside of her office. I will never forget the shrill and incredulous voice of the reporter as she reported – in real time – the collapse of the first tower. I was leaning against a wall and slid down, landing in a swat. Shortly after, we all decide to leave. No one wanted to be on the 19th floor of a Manhattan building. Airplanes could be heard outside and no one knew the extent of the attack. We left in groups. I walked downtown against a stream of people to my friend’s art studio on 28th and Broadway. Along the way I saw the remaining tower down 5th avenue. By the time I got to 28th Street, it was gone. I was able to contact my grandmother in Queens and my brother in Manhattan. All were ok. My parents were in Africa, safer among the lions. I was not able to contact my husband, who was on Long Island. We listened to the radio the entire afternoon (my friend had no TV in her studio). Around 4 pm, I decided to walk to Penn Station to see if I could get a train back to Bayside, Queens, where I lived at the time. To my surprise, trains were running. Twenty minutes later I rode off of the island of Manhattan in an eerily silent train watching the bellowing black smoke where the Twin Towers once stood.

I eventually reached my husband, who had tried to get home, but was stopped in Westbury (no traffic west of Westbury). He would have to sleep over at a friend’s house on LI. I watched the footage alone and eventually went to sleep. At 2:30 a.m. my husband walked through the door – he didn’t want to be away and tried driving back again. This time no one stopping traffic.

Those first few days following 9/11, Ground Zero was accessible. My brother went down and walked around. I stayed away. I was worried about the air quality. If it were just me, I might have gone, but on the afternoon of September 10th, I had been given the joyous news that I was pregnant with my first child. At the time, I thought I would have stopped trying if I had not yet conceived. But in retrospect, I think I would have continued. If you don’t go on with your life, the terrorists win.

September 15, 2011 @ 12:10 am

It was my youngest son’s first day of preschool. A very hard drop off, to say the least. Here on the west coast, we were very far removed from the smoke and fire but we all felt it strongly as we, too, watched TV “like zombies” for days. My kids have moved on but for my husband and myself, the world is definitely very different. This is our generation’s Pearl Harbor.

September 30, 2011 @ 12:32 am

It was my first week as a freshman at NYU. I saw the fires and shortly thereafter, watched the second plane hit. I stopped watching after I realized the little black dots I’d see periodically falling were people. I lived on 14th St. Union Sq at the time, in NYU housing. A few days later we were standing on line at the local United Artists theatre; they were offering free movies and popcorn. The smoke was so thick, I couldn’t see my hands in front of mine. And the smell…10 years later and I still don’t think I’ll ever forget that smell.

I also remember thinking…the entire world is mourning us now, and we’re going to screw this up. I thought we should take the high rode and not retaliate. Instead, spend money at home building green and renewable resources. Stop buying foreign oil…that will hurt them far more than any war. Instead, we’re a decade out with no end in sight to a war we can’t win, and trillions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of lives gone.

War doesn’t decide who’s right. It decides who’s left.

Sometimes I hate being right.