A Conversation with an Exceptional Mother About Her Exceptional Daughter

Well, I’ve had a fun couple of weeks! I was about to publish the post here, until my website decided to misbehave, which you may have noticed if you tried to check in recently and got one of those chipper “service not available!” messages.

That’s when the wonderful Elizabeth Kricfalusi of Tech for Luddites (and a writer-friend-and-fellow-West-Wing devotee of mine) stepped in to help me fix the site’s issues. Before I called on her, I’d been trawling Word Press tutorials and info online, but that’s like giving me an IKEA flat pack box, instructions in the original Swedish, and a hearty “good luck!” Not my language. So I got smart and actually hired Elizabeth to rebuild and fix. As you can see, it’s all back to shiny good website health. Elizabeth is my new favorite person in the world, and you should click over to Tech for Luddites for answers to all sorts of techy questions you were too embarrassed to ask about.

And now back to your regularly-scheduled post:

A conversation with author Jennifer Lawler

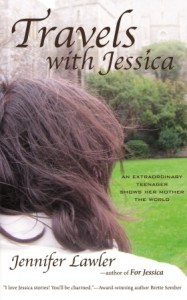

I’ve known writer, editor, agent and mother Jennifer Lawler for quite a few years. I’m trying to think of some way to describe her that doesn’t sound trite (you know, like, “she’s an inspiration…”), but … oh, heck. She’s an inspiration to me (and she ended up introducing me to my book agent, so there’s that!). Jennifer is the author of many books and the divorced mother of a teenage girl, Jessica. Travels with Jessica, her latest book is about … well, traveling with Jessica.

But Jessica isn’t just any teenager, which is why Jennifer isn’t just any mom.

Jessica was born with a condition called tuberous sclerosis (described to Lawler as a “massively deformed brain”), and when she was still a baby her doctors told Lawler and her now-ex husband that to keep their baby girl alive and stop her near-constant seizures, resecting her brain was the only option.

The surgeons called it “resection.” Lawler labels it her own way, calling the procedure “taking half your daughter’s brain, tossing it away…”.

You wouldn’t think having a teenager like Jessica would prompt you to say, “heck, yeah, let’s go to Italy!” But you don’t have a teenager like Jessica. Going to Italy was her idea, and the resulting series of trips became fodder for a series of essays that Lawler gathered into Travels with Jessica. It will teach you a thing or two about Italy, sure; and about the Washington, D.C. metro system. But it’ll also teach you a thing or two about expectations turned on their heads, about what’s universal about mothers and children, and what’s utterly special about this mother and daughter.

I asked Jennifer Lawler about parenting a teen, not to mention a teen with special needs, and not to mention one who wants to go to Italy. Here’s our conversation:

Jessica is your only child, your only experience parenting a teen. But she’s not like other teens. What has that been like for you?

My parenting experience got stuck at “almost grown up.” In many ways, Jessica is a teen like every other teen. She has her moods, and she rolls her eyes at half of what I say, and she thinks I’m a complete dork. She wants to have a job, and a family, and all of that, and she likes a boy at school, and she wishes she could get her driver’s license. But in other ways, she’s a lot younger. Like she wants to hold my hand crossing the street and she’s still really squeamish at the idea of kissing that boy she likes, and she needs a lot of help with the activities of daily living. So I’ve been giving baths for a lot longer than most parents do. And I’m never going to experience things like Jessica applying to colleges or getting her dream job in New York or most of what we might consider typical young adult life milestones.

The thing about Jessica is that I knew from the beginning that our life was going to be very different from what I had expected and from what most people experience, so I never had a strong sense of the way things should be. I had to throw all those fantasies out the window when she was just a baby. That doesn’t mean I don’t have moments where I wish her life could be different, it just means that I had to parent who she is, not who I wanted her to be, from the very start. I see a surprising number of parents who don’t recognize this until their kids are a lot older and suddenly they don’t have the kid they thought they had (or wish they had).

I lost the parenting competition a long time ago. It’s surprisingly freeing. My kid is never going to Harvard, never going to win Olympic gold, or anything like that. She’s also never going to let me down just because she is who she is.

Every parent, no matter what, is going to discover – sooner or later, in small ways or in major ones – that the kid they have doesn’t match the one they fantasized about and created hopes for. In your case, the realization that fantasy wouldn’t match reality came instantly and devastatingly. What message do you think you have to share with parents of typical children?

It’s human nature to have hopes for our children, to fantasize about what their lives are going to be like, and who we will be as parents. If I have a message, it’s that you can’t let those fantasies rule your life. I feel sorry for people who get so stuck on what they wish they had that they can’t see this amazing child that they do have. I see amazing children everywhere, and their parents are harassing them to death. It seems a lot of parents think, “Life would be easier if you [the child] were different,” and they don’t want life to be hard for their children.

But here’s the thing. Jessica is very different from other children, but it has never actually occurred to her that this is a bad thing. I mean, she certainly hates spending as much time in the hospital as she does, but she sort of treats that as the cost of admission to the world, which to her is this big amazing place that she wants to experience as much of as she can. I’m the one who’s making judgments about how difficult her life must be and how I wish it were easier. She cares jack squat about easier.

I told a friend the other day that if I could wave a magic wand and make Jessica “normal” I wouldn’t do it. My friend found that frankly impossible to believe. But it’s true. Do I wish Jessica didn’t have to suffer? Of course. We all wish our children didn’t have to experience pain. Do I think I could take away what has made her who she is and still have the same daughter? No. She’s perfect just the way she is. I’ve always called her my Buddha baby. I learn so much from her.

Tell me what triggered the travel bug for you and Jess.

I have always wanted to do more overseas travel than I have, but for years I was unwilling to do it with Jessica. It just seemed too hard, logistically speaking. Plus there’s always the risk that she’ll have a medical emergency and I’ll be stuck in a hospital thousands of miles from home trying to communicate in a language I don’t speak. We did some domestic travel, which we both enjoyed, but it didn’t really scratch my travel itch.

I kept thinking “someday.” Then a few years ago when I was talking to Jess about planning a vacation, the idea of traveling overseas was suddenly on the table. It was a combination of my not wanting to do our usual vacation to Disney World and Jess hearing other people talking about their overseas trips. I kept thinking of all the reasons why it would be hard. Jess wanted to go to Italy, I think because she’d heard a friend of her dad’s talking about it, and the idea of traveling with Jess to a country where I don’t speak the language was intimidating—and I’m not a person who’s intimidated by much.

When you have a child like Jessica, you worry that she’s going to encounter people who ridicule her or who don’t know how to deal with her. She doesn’t understand everything a typical teenager does and this can frustrate others, who take it out on her. When people realize she’s cognitively impaired, they sometimes act like she isn’t even there. People can be cruel about differences. But in our town, everyone knows Jessica and understands how to interact with her, and when we travel to, say, New York to be with friends, we’re with friends. Or if we go to Disney World, the staff there is (usually) trained to understand how to engage with people of all types. I had no idea what it would be like, emotionally speaking, to bring her out into the wider world and I had very serious reservations.

For some reason, though, traveling overseas mattered a lot to Jessica. I think the fact that it was a challenge was what made it matter to her; I think she felt that if she could convince me that we could to this, it would open up the whole world to her. And she was right.

What surprised you most about your travels with your daughter?

How competent Jessica turned out to be, and how kind everyone was. Jessica has this way of bringing out the best in people, even or maybe especially, total strangers.

The more we traveled, the more competent she became with navigating the world. She actually relies on me a lot more when we’re at home than she does when we’re traveling. One of the things I worried about was how anxious she gets when I’m not sure what I’m doing and of course when I’m in unfamiliar places, I spend a lot of time not being sure what I’m doing. But Jessica has learned to be a good sport about this. And we have these inside jokes now, like how I can’t get on a plane without breaking a fingernail. So we’ll sit down in our seats and I’ll reach into my bag for a book and she’ll say, “You better get out your emery board, too!” And we’ll both crack up laughing.

What I’ve learned from our travels is to be a little more selfish. In the past, I focused on what Jessica would enjoy (thus all those trips to Disney World). When we went to England, I had really strong feelings about what I wanted to do, and for the first time in our travels, I insisted that we do all the things I wanted to do. Jess was totally fine with that. Sometimes she was bored out of her skull, but she knew that these things mattered to me and she let me enjoy them. She even tried to figure out what made me interested in them.

One of the things I wanted to do was see a Shakespeare play in London, and so Jess and I agreed that I’d see Shrek: The Musical with her if she’d see Twelfth Night with me. I didn’t expect her to understand the play at all, though I’d bought her a book about it and told her the basic plot. So we’re watching Twelfth Night and I’m sure she’s about to fall asleep when I hear her laughing out loud. I turn to look at her: She’s laughing so hard she’s got tears in her eyes.

“That was ridiculous!” she told me over and over afterwards. Jessica laughing at Twelfth Night is one of those things I’m going to remember when I’m a hundred and ten.

Author Jennifer Lawler

To buy Travels with Jessica in paperback or Kindle versions, go to Amazon. It’s also available for the Nook through Barnes & Noble. Other ebook versions can be found here.